SMR Neurofeedback: The Calm-Alert Brainwave That Trains Sleep, Focus, and Self-Control

If you're going to understand neurofeedback, you start with one rhythm: SMR — sensorimotor rhythm.

SMR is a narrow band of low beta ((\sim)12–15 Hz) generated over the sensorimotor strip (the ear-to-ear band of cortex that handles sensation and movement). In practice, it behaves like "alpha for your motor system": not sleepy, not wired — quiet body, bright mind.

It's also historically important. SMR is the protocol that helped launch modern EEG biofeedback, and it's still one of the most reliable "first-line" training targets for sleep, anxiety stabilization, and impulse control.

What SMR is (and what it isn't)

- SMR is not "relaxation." Relaxation usually means higher alpha (posterior dominant rhythm) and a general downshift in arousal.

- SMR is "stillness + readiness." It's the neural signature of motor inhibition without cognitive shutdown.

- SMR is not a broad beta band. It's a specific strip rhythm; you train it best at C3/C4/Cz (sensorimotor cortex).

If you want a clean mental image:

The cat on the windowsill: body perfectly still, attention locked on the world. That "quiet motor + stable attention" state is SMR territory.

Why SMR works: the thalamocortical gating mechanism

SMR training modulates thalamocortical gating through spindle-related circuits. The thalamic reticular nucleus acts as the primary gatekeeper, regulating signal flow between thalamus and cortex. When this switchboard is "leaky," you get sensory overwhelm, startle reactivity, restless motor output, sleep fragmentation, and scattered attention.

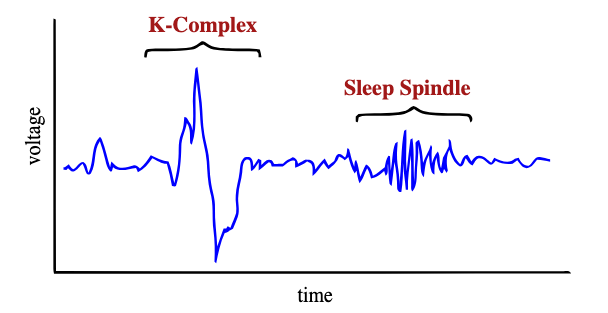

SMR operates through the same thalamocortical circuitry that generates sleep spindles — specifically the 12-15 Hz oscillations generated by GABAergic neurons in the reticular nucleus. Training SMR strengthens these inhibitory circuits, making the thalamic "brake" more efficient at filtering noise before it reaches conscious awareness.

This is why SMR works for both sleep and attention: you're training the neural generators that control whether competing signals get through or get filtered out. The mechanism is precise — enhanced thalamocortical inhibition without cognitive suppression.

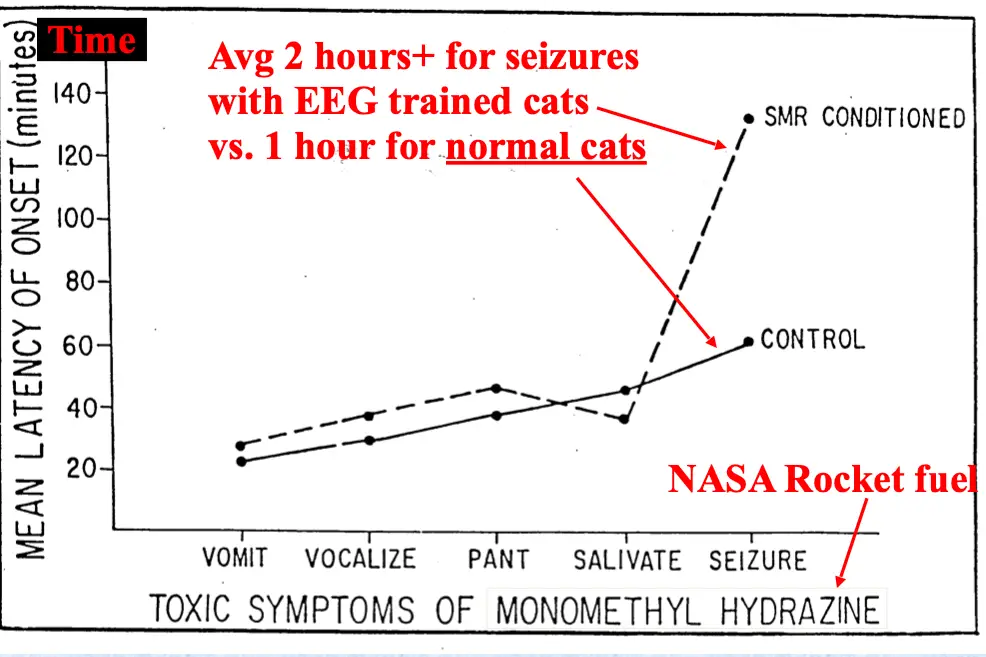

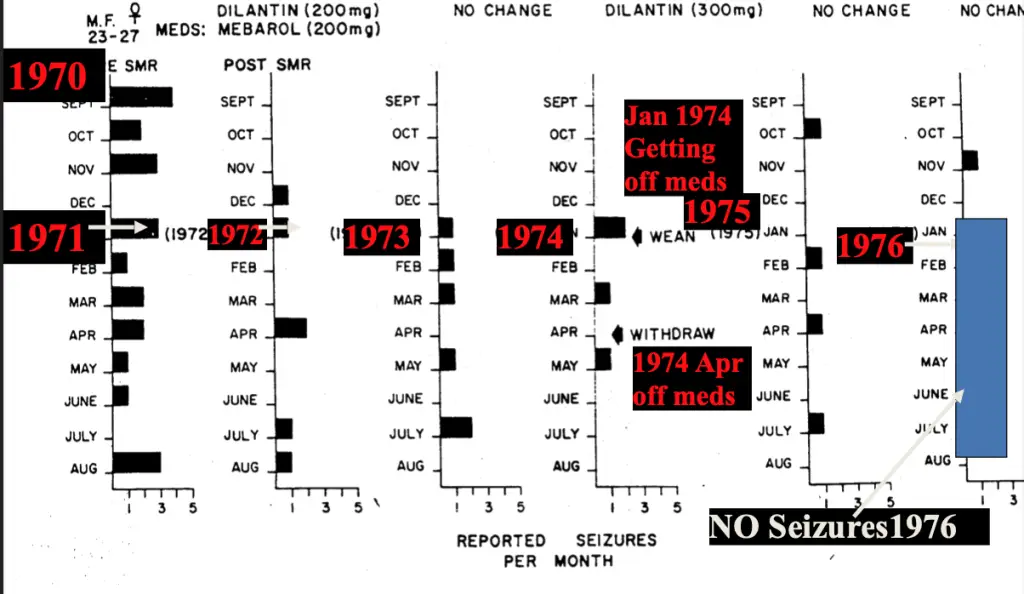

The founding story: Sterman's cats and the seizure clue

SMR didn't become famous because someone theorized it would help. It became famous because of an accident of science.

Barry Sterman (UCLA) was studying the effects of rocket fuel exposure in cats. Some cats were unexpectedly seizure-resistant — and it turned out they had previously been trained to produce SMR-like activity. That observation helped kick off decades of work on SMR as a stabilizing rhythm (Sterman & Fairchild, 1967; Sterman & Egner, 2006).

Here are two reference figures showing the classic Sterman findings:

SMR and sleep: spindles, stability, and "staying down"

SMR overlaps directly with sleep spindle physiology — they're different expressions of the same thalamocortical circuit. The key insight: daytime SMR training literally strengthens the neural generators that produce nighttime sleep spindles.

Hoedlmoser et al. (2008, Sleep) showed SMR neurofeedback at Cz increases sleep spindle density with medium to large effect sizes. Ten sessions of SMR conditioning reduced sleep onset latency from 40 to 19 minutes while significantly enhancing spindle metrics during Stage 2 sleep.

This spindle enhancement matters because sleep spindles serve dual functions: they gate sensory input (keeping you asleep) and facilitate memory consolidation through thalamocortical synchronization. When you strengthen the SMR-spindle circuit through daytime training, you improve both sleep maintenance and next-day cognitive performance.

The therapeutic targets are:

- sleep onset latency (taking too long to fall asleep)

- hyperarousal insomnia (tired but wired)

- light sleep / frequent awakenings

- memory consolidation deficits

SMR and ADHD: the "brakes" protocol

SMR training addresses a core ADHD mechanism: deficient thalamocortical gating. When the thalamic switchboard can't properly filter competing signals, you get the classic ADHD triad — inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity.

The dose-response relationship is clear: 20-40 sessions at 2-3 sessions per week produces lasting changes in self-control behaviors. The optimal training window is 20-30 minutes of active SMR conditioning per session. Clinical evidence shows improvements maintain for 6-24 months without any maintenance sessions once gains are consolidated (Arns et al., 2014, Clinical EEG & Neuroscience).

In ADHD populations, sleep quality improvements statistically mediate reductions in inattention symptoms (but not hyperactivity/impulsivity), suggesting the SMR-spindle pathway specifically targets vigilance networks rather than motor control circuits (Gevensleben et al., 2012, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry).

In plain language:

- Low SMR → harder to inhibit movement, harder to keep attention steady, more "popcorn brain."

- Training SMR → strengthens thalamocortical inhibition, stabilizes attention networks, improves response control.

The mechanism isn't just "calming" — it's selective enhancement of inhibitory control while preserving cognitive alertness.

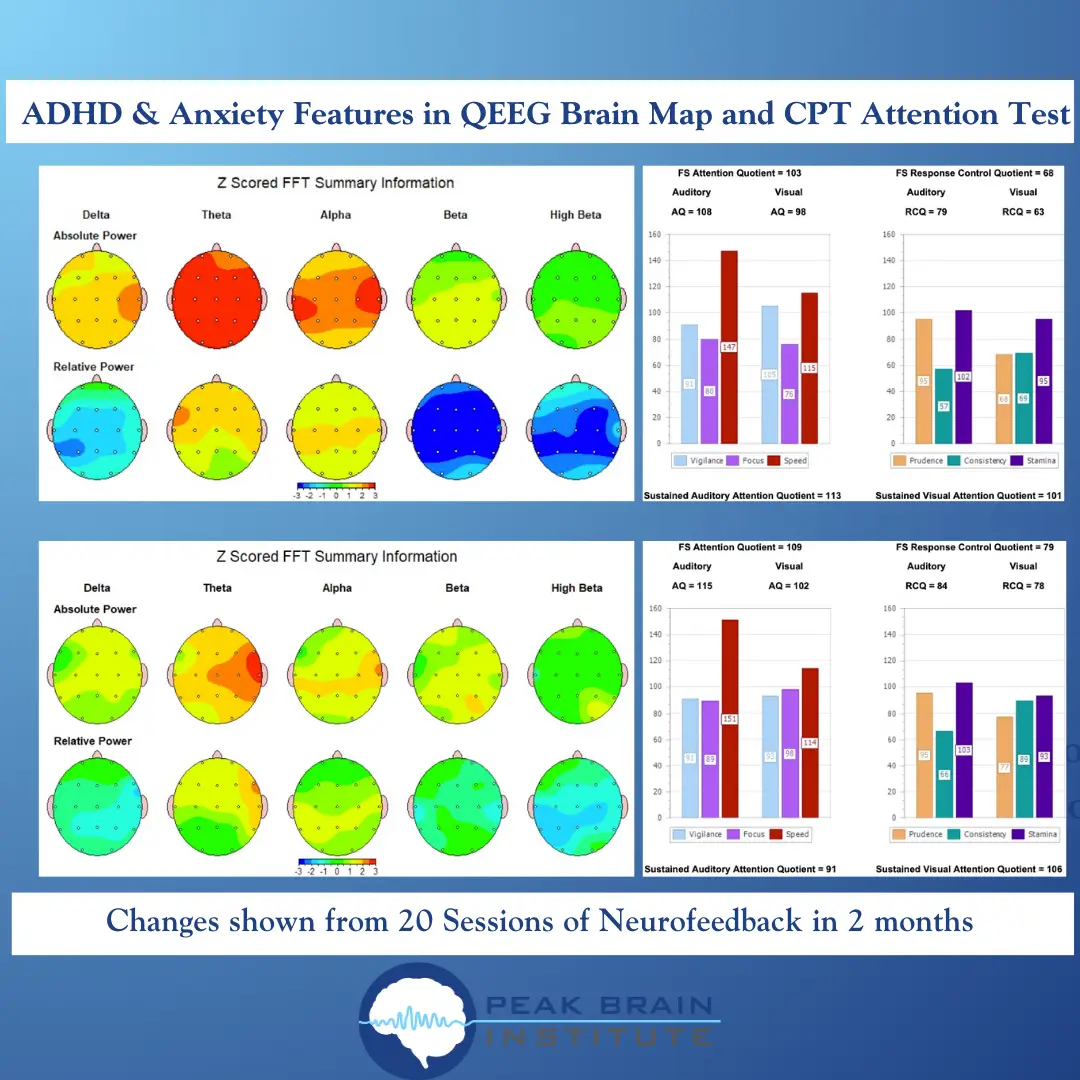

What "results" can look like (a classic outcome pattern)

When SMR-focused training is done well (and paired with good protocol selection), you often see a familiar pattern:

- The EEG shifts toward a more regulated baseline (less "noisy" slow activity, more stable rhythms).

- Attention and response control metrics improve on a CPT-style task.

Here's a representative "before/after" style outcome figure:

What an SMR session looks like (practical, not mystical)

SMR training is basic EEG biofeedback:

- Place an electrode at C3, C4, or Cz (sensorimotor strip).

- Reference to an ear (or mastoid) and use a ground.

- Reward a narrow band around SMR (commonly ~12–15 Hz; often individualized).

- Inhibit slow activity (theta) and very fast activity (high beta) to reduce artifacts and "tension training."

The frequency specificity matters. Training in the narrow 11.75-14.75 Hz range maximizes overlap with thalamocortical spindle circuits while avoiding arousal-related beta contamination. Broader beta training doesn't produce the same sleep spindle enhancement or memory consolidation benefits.

Protocol individualization is key. Your individual alpha peak frequency (iAPF) predicts optimal SMR training bands — people with lower iAPF often need slightly lower SMR targets (11-13 Hz) while higher iAPF individuals train better at 13-15 Hz (Bazanova & Vernon, 2014, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews). This personalization significantly improves clinical outcomes compared to standard frequency ranges.

If you train too fast for your system, you'll often feel wired later (even if you feel calm during the session). If you train too slow, you can get sleep disruption or "groggy brain." This is why good neurofeedback is iterative: you observe the after-effects and adjust.

Who SMR is best for (and who should be cautious)

Often a good fit:

- insomnia with hyperarousal physiology

- anxiety/panic stabilization (as a first step)

- ADHD/impulsivity features (especially when sleep is also an issue)

- concussion/post-concussion "overstimulation" patterns (case-by-case)

- memory consolidation issues linked to poor sleep quality

Be careful / don't freestyle:

- seizure disorders (work with an experienced clinician)

- bipolar spectrum instability (protocol selection matters)

- severe trauma presentations (stabilize first; avoid "deep" protocols too early)

Bottom line

If neurofeedback had a "foundation protocol," it's SMR.

It's not magic. It's a training target that maps onto a real mechanism: enhanced thalamocortical gating through spindle circuit strengthening. When you get that right, sleep gets easier, attention gets steadier, memory consolidation improves, and the nervous system stops behaving like it's constantly bracing for impact.

The beauty of SMR is its dual action — you're training a daytime attention state that directly enhances nighttime sleep architecture through the same neural circuits.

References (selected)

- Sterman, M. B., & Fairchild, M. D. (1967). SUBCONVULSIVE EFFECTS OF 1,1-DIMETHYLHYDRAZINE ON LOCOMOTOR PERFORMANCE ON THE CAT: RELATIONSHIP OF DOSE TO TIME OF ONSET. Defense Technical Information Center. https://doi.org/10.21236/AD0664549

- Sterman, M. B., & Egner, T. (2006). Foundation and practice of neurofeedback for the treatment of epilepsy. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9002-x

- Hoedlmoser, K., Pecherstorfer, T., Gruber, G., Anderer, P., Doppelmayr, M., Klimesch, W., & Schabus, M. (2008). Instrumental conditioning of human sensorimotor rhythm (12–15 Hz) and its impact on sleep as well as declarative learning. Sleep, 31(10), 1401–1408.

TAGS

Related Articles

Why Does My ADHD Kid Make Me Yell? (And What to Do About It)

You asked your child to put on their shoes fifteen minutes ago. They're still sitting on the floor, one shoe on, building a Lego tower, completely oblivious to the fact that you're late for school.

Biohacking Sleep: Optimize Your Rest for Peak Performance

You know sleep matters. You've read the articles about how it affects memory, metabolism, mood, immune function, and basically every system in your body.

New Year, New Habits: Neuroscience of Making Them Stick

Most New Year's resolutions fail by February. Not because you lack discipline. Because you're trying to use willpower (prefrontal cortex) to fight automatic behavior (basal ganglia). That's like tryin...

About Dr. Andrew Hill

Dr. Andrew Hill is a neuroscientist and pioneer in the field of brain optimization. With decades of experience in neurofeedback and cognitive enhancement, he bridges cutting-edge research with practical applications for peak performance.

Get Brain Coaching from Dr. Hill →