Biohacking with EEG Phenotypes: Predicting Function from EEG Characterization

Introduction: Clinical Database Development of EEG

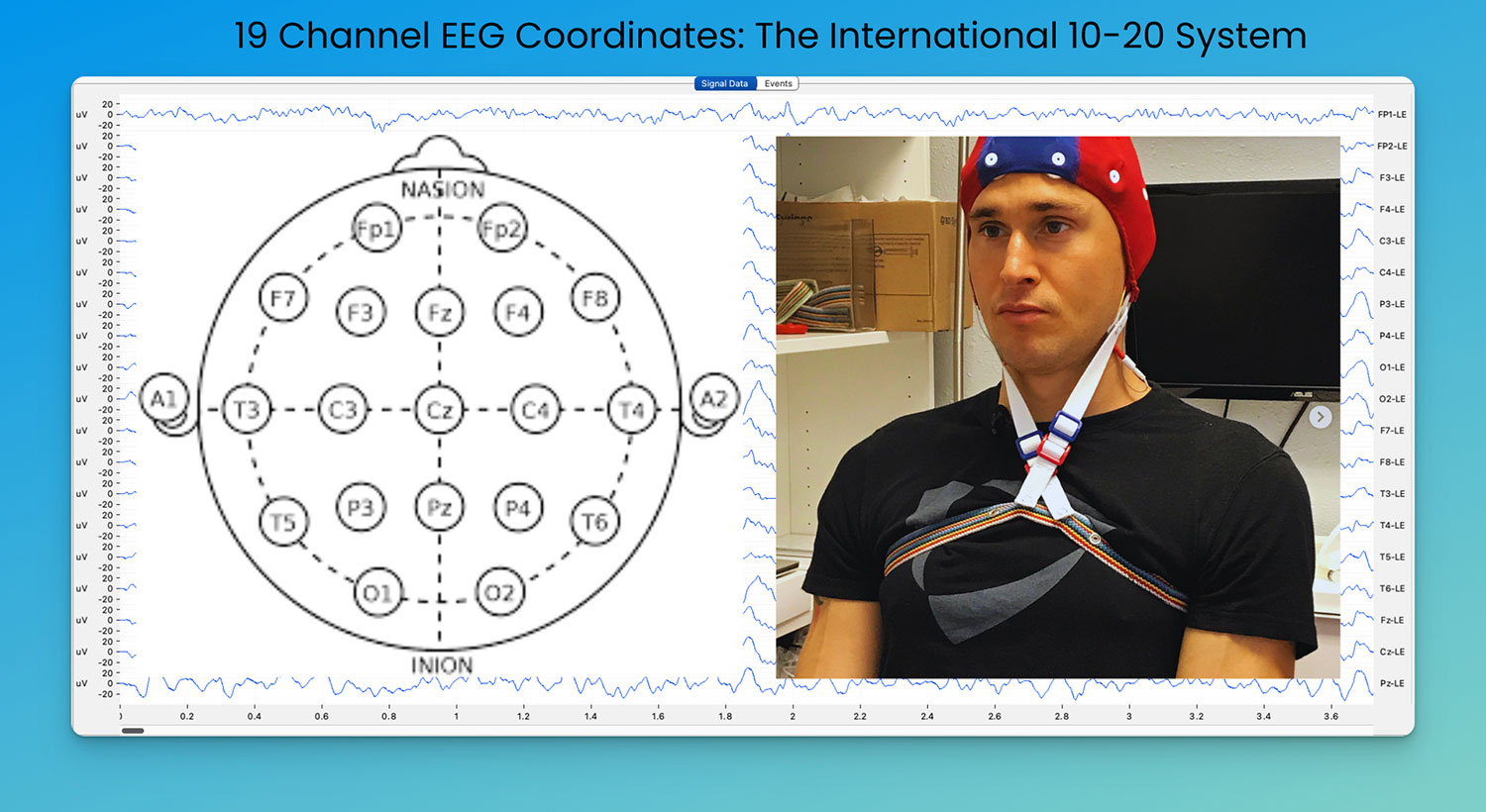

Since Hans Berger recorded the first human EEG in 1924, clinical electroencephalography has transformed from detecting gross brain dysfunction to identifying subtle patterns that predict treatment response. Modern QEEG analysis reveals that specific brain activity patterns—called phenotypes—cross diagnostic boundaries and guide intervention selection more accurately than DSM categories alone.

Unlike traditional approaches focused on "normal versus abnormal" EEG, phenotypes represent stable neurophysiological patterns with clear genetic and environmental influences. Research by Johnstone, Gunkelman, and Lunt (2005) established these as intermediate phenotypes linking genes to behavior—patterns that remain consistent across time and predict treatment outcomes.

Key Aspects:

- Linking specific brain patterns to effective interventions, reducing variability in treatment outcomes

- Moving beyond DSM categories to identify predictive neurophysiological markers with 85-90% accuracy

- Phenotypes as stable, interpretable patterns connecting thalamocortical circuits to treatment response

- Evidence-based methods using quantitative EEG to guide intervention in neurobehavioral conditions

Table of Contents

Core Concept: What is an EEG Phenotype?

EEG phenotypes represent stable patterns of thalamocortical regulation visible on brain recordings. Unlike biomarkers that may lack treatment specificity, phenotypes integrate multiple features into consistent patterns that predict intervention response. These patterns reflect fundamental organizational principles—how your brain regulates attention, arousal, sensory processing, and emotional control.

Definition and Fundamentals

Research demonstrates EEG phenotypes reflect genetic architecture and environmental influences on brain development. Arns et al. (2008, Journal of Integrative Neuroscience) showed frontal theta patterns predict stimulant response with 85% accuracy, while Clarke et al. (2001, Clinical Neurophysiology) identified distinct ADHD subtypes based on EEG patterns rather than behavioral symptoms.

Key Characteristics:

- Semi-stable neurophysiological patterns linked to COMT, GABAA receptor, and dopamine transporter genes

- Differentiation from transient EEG features that lack predictive value across sessions

- Examples: Low-voltage fast EEG reflects GABAA receptor function; frontal theta indicates dopaminergic underactivation

- Cross-disorder relevance—identical patterns appear in ADHD, concussion, and sleep apnea despite different symptom presentations

- Correlation with continuous performance testing (CPT), family history, and specific symptom clusters

The Phenotype-Feature-Biomarker Framework

Understanding EEG patterns requires distinguishing between basic observations and clinically meaningful patterns. This hierarchical framework, validated across multiple research centers, moves from simple measurements to actionable insights about brain function and treatment selection.

EEG Features

Basic EEG features represent individual measurements—increased theta power, beta amplitude, or alpha frequency. These isolated measures show limited clinical utility because they lack context about regulatory networks and functional significance.

Core Elements:

- Frequency band power measures (theta: 4-7 Hz, alpha: 8-13 Hz, beta: 13-30 Hz)

- Transient patterns requiring integration with other measures

- Quantitative metrics from resting EEG recordings

- Raw amplitude and coherence values

Biomarkers

Biomarkers demonstrate stability across individuals and time but may lack consistent treatment implications. Slow individual alpha peak frequency exemplifies this—reliable measurement but variable clinical significance depending on cortical location and network context.

Key Aspects:

- Test-retest reliability coefficients >0.70 across sessions

- Individual alpha peak frequency ranges from 7.5-12.5 Hz in healthy adults

- Lacks direct treatment implications without phenotypic context

- Contributes to clinical database development for population comparisons

Phenotypes

Phenotypes integrate multiple biomarkers and features into meaningful regulatory patterns. Beta spindles at 14-18 Hz indicate GABAergic influences on cortical inhibition, while frontal theta excess reflects dopaminergic insufficiency in anterior cingulate-prefrontal circuits (Monastra et al., 1999, Neuropsychology).

Essential Characteristics:

- Network-level patterns integrating thalamocortical, corticolimbic, and default mode activity

- Inter-rater reliability coefficients >0.85 between trained clinicians

- Predictive validity for medication response, neurofeedback outcomes, and cognitive performance

- Statistical validation across independent research samples

Core EEG Phenotypes with Strong Evidence Base

Four phenotypes demonstrate high inter-rater reliability (Kappa >0.90) and clear treatment implications across multiple validation studies. These patterns show consistent relationships with specific neurotransmitter systems and predict intervention outcomes better than clinical symptoms alone.

Low Voltage Fast (LVF)

LVF reflects altered GABAergic function linked to specific genetic variants on chromosome 15q11-q13. This phenotype shows beta activity >20 Hz with reduced amplitude across all frequency bands, indicating hyperactive thalamocortical circuits with insufficient inhibitory regulation.

Key Characteristics:

- Associated with GABAA receptor subunit genes (GABRB3, GABRA5, GABRG3)

- High comorbidity with alcoholism, anxiety disorders, and benzodiazepine tolerance

- May emerge after concussion or traumatic brain injury affecting GABAergic interneurons

- Treatment implications: Variable stimulant response; improved outcomes with GABAergic modulators

- Quantitative criteria: Beta power >+1.5 SD, total power <-1.0 SD across multiple electrodes

Frontal Slow

Frontal slow activity represents the most clinically significant pattern for predicting stimulant response in attention-related conditions. This phenotype reflects dopaminergic insufficiency in mesocortical pathways connecting ventral tegmental area to prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate.

Essential Features:

- Elevated frontal delta (1-3 Hz) and theta (4-7 Hz) indicating cortical hypoarousal

- Predicts positive stimulant response in 85% of cases (Chabot et al., 1999, Journal of Child Neurology)

- Correlates with sustained attention deficits on continuous performance tests

- Distinguished from slowed alpha—different circuits, different treatments

Slowed Alpha Peak Frequency

This phenotype involves individual alpha frequency <8.5 Hz, often misclassified as theta in traditional analyses. Associated with COMT val/val genotype affecting dopamine metabolism, this pattern indicates different cortical timing mechanisms than frontal slow activity.

Critical Aspects:

- Linked to COMT val158met polymorphism affecting prefrontal dopamine clearance

- Predicts poor stimulant response—may worsen attention and increase anxiety

- Requires individual peak identification, not standard frequency band analysis

- Treatment implications favor non-stimulant approaches and alpha frequency training

Spindling Excessive Beta

Beta spindles represent distinct 14-18 Hz bursts reflecting GABAergic interneuron activity and thalamic reticular nucleus function. Unlike general beta excess, spindles show specific morphology—brief bursts with rapid onset/offset—indicating anxiety-related cortical hypervigilance.

Defining Features:

- Burst duration 0.5-2.0 seconds with >50% amplitude modulation

- Linked to benzodiazepine receptor sensitivity and GABA-A function

- Clinical correlates: hypervigilance, anxiety, sensory hypersensitivity

- Treatment response to GABAergic modulators, poor stimulant tolerance

When raw EEG patterns are analyzed against population databases, we see standardized "maps" of deviations from typical functioning. The patterns above translate into quantitative analyses:

Laplacian QEEG analysis (eyes closed)

Linked Ears QEEG analysis (eyes closed)

Broader Conserved EEG Patterns

Beyond core phenotypes, several patterns show consistent behavioral relationships. While not meeting full phenotype criteria, these patterns provide insights into emotional regulation, attention control, and sensory processing that guide both clinical intervention and personal optimization strategies.

Patterns with Potential

Frontal Alpha Asymmetry

Frontal alpha asymmetry reflects differential activation in approach-avoidance motivational systems. Left frontal alpha power inversely correlates with prefrontal activation—less alpha indicates more activity in behavioral approach systems.

Key Aspects:

-

Approach systems (left frontal activation)

-

Associated with dopaminergic activity in left prefrontal cortex

-

Correlates with positive affect, goal-directed behavior, resilience

-

Better sustained attention and task engagement

-

Avoidance systems (right frontal dominance)

-

Connected to withdrawal behaviors and threat sensitivity

-

Increased right frontal activation during negative emotion processing

-

Risk factor for anxiety disorders and depression (Davidson, 1998, Psychophysiology)

-

Clinical implications

-

Asymmetry >0.15 ln units predicts mood disorder vulnerability

-

Neurofeedback targeting alpha asymmetry shows 65% response rates

-

Meditation practices can normalize asymmetry patterns over 8-12 weeks

Other Significant Patterns

-

Temporal alpha elevations

-

Correlate with auditory processing sensitivity and social anxiety

-

May indicate temporoparietal junction hyperactivation

-

Persistent alpha with eyes open

-

Suggests arousal system dysfunction or default mode network intrusion

-

Often seen in attention difficulties and daydreaming tendencies

-

Theta/Beta Ratios

-

Ratio >4.5 indicates cortical underarousal in ADHD populations

-

Predicts stimulant response with 78% accuracy (Monastra et al., 1999)

Cortical Hub Features

Network neuroscience identifies key cortical hubs that integrate information across brain regions. These hubs show consistent EEG signatures that can be monitored and trained through specific interventions.

Key Hubs and Functions:

-

Anterior Cingulate (Fz, FCz)

-

Error detection and conflict monitoring via theta oscillations (4-7 Hz)

-

Emotional regulation through connections to amygdala and prefrontal cortex

-

Target for attention training and emotional regulation protocols

-

Posterior Cingulate (Pz)

-

Default mode network hub showing alpha/theta during rest

-

Self-referential processing and autobiographical memory integration

-

Excessive activity linked to rumination and depression

-

Left Precentral Gyrus (C3)

-

Motor planning and procedural learning via mu rhythm suppression

-

Action preparation reflected in 8-12 Hz sensorimotor rhythms

-

Training target for motor skill acquisition and ADHD

-

Right Temporoparietal Junction (P4, T4)

-

Social cognition and theory of mind processing

-

Attention switching between internal and external focus

-

Hyperactivation in autism spectrum and social anxiety conditions

Additional Examples - ADHD and Anxiety

Phenotypes are impacted by medication: Example with Concerta

Clinical Applications and Treatment Selection

Translating EEG phenotype understanding into clinical practice requires standardized technical approaches and careful interpretation of network-level patterns. Success depends on proper pattern recognition, database comparisons, and integration with genetic and performance measures.

Pattern Recognition and Analysis

Effective phenotype identification requires standardized acquisition and analysis procedures. Technical consistency enables reliable pattern recognition across sessions and treatment monitoring over time.

Technical Considerations

- Phenotype identification requires matched filtering (0.5-50 Hz), artifact rejection (<±100 μV), and reference montage

- Raw EEG visual analysis remains the foundation—digital processing enhances but doesn't replace pattern recognition

- Database comparisons provide population context but individual variation within normal ranges may be clinically significant

- Test-retest reliability >0.80 required for treatment planning and outcome monitoring

Database Considerations

- Normative databases compare to typical, not optimal functioning—outliers may represent strengths, not deficits

- Individual alpha frequency must be identified before frequency band analysis

- Pattern stability across multiple sessions confirms phenotype versus transient state

- Age-matched comparisons essential—alpha frequency decreases 0.1 Hz per decade after age 20

QEEG in Treatment Selection

EEG-guided treatment selection outperforms symptom-based approaches for medication and neurofeedback protocols. Suffin and Emory (1995, Clinical Electroencephalography) demonstrated 78% medication response prediction using QEEG versus 65% with clinical symptoms alone.

Medication Selection Using EEG Phenotype Approaches

Phenotype-guided medication selection reduces trial-and-error prescribing and predicts side effect profiles before treatment initiation.

Stimulant Response Patterns:

- Frontal theta phenotype predicts 85% positive response to methylphenidate or amphetamines

- Low voltage fast shows 60% response rate but higher anxiety side effects

- Slowed alpha peak frequency indicates 25% response rate—alternative treatments preferred

- Beta excess requires monitoring for overstimulation and sleep disruption

Antidepressant Response Patterns:

- Frontal alpha excess predicts SSRI response in 85% of cases (Spronk et al., 2011, Journal of Affective Disorders)

- Right frontal alpha asymmetry suggests better response to bupropion than SSRIs

- Beta spindle patterns may require anxiolytic augmentation with antidepressant treatment

- Posterior cingulate hyperactivity correlates with rumination-focused therapy benefits

Treatment Monitoring:

- EEG changes within 1-2 weeks predict eventual treatment outcome

- Theta/beta ratio normalization indicates stimulant engagement and optimal dosing

- Alpha asymmetry changes track mood improvement before symptom reports

- Beta spindle reduction correlates with anxiety symptom improvement

Personal Understanding Through EEG Phenotypes

Understanding Your Brain's Patterns

Individual brain patterns provide specific insights into cognitive timing, attention capacity, emotional regulation style, and sensory processing preferences—information that enables targeted optimization strategies.

Individual alpha peak frequency correlates with:

- Cognitive processing speed—higher frequency (>10 Hz) enables faster information processing

- Working memory capacity and learning efficiency

- Optimal meditation frequency for relaxation training

Frontal beta patterns inform:

- Sustained attention duration—excess beta may indicate overeffort and quick fatigue

- Cognitive control strategies and mental flexibility

- Stress reactivity and anxiety vulnerability

Theta/alpha ratios relate to:

- Default mode network regulation and mind-wandering tendencies

- Creative insight capacity and divergent thinking

- Memory consolidation efficiency during rest and sleep

Key Domains for Self-Understanding

Attention & Focus

Understanding attention patterns enables personalized cognitive strategies:

- Frontal theta patterns suggest stimulating environments enhance focus

- Beta excess indicates need for relaxation before cognitively demanding tasks

- Alpha peak frequency determines optimal work session duration (8-12 Hz: 45-90 minutes)

- Sensorimotor mu rhythm predicts motor learning capacity and physical skill acquisition

Stress & Arousal

Arousal regulation can be optimized through pattern-specific strategies:

- Beta spindle patterns require stress management before performance tasks

- Alpha asymmetry patterns predict which meditation styles work best (left dominance: active meditation; right dominance: passive approaches)

- Frontal alpha levels indicate optimal caffeine timing and dosing

- Posterior cingulate activity predicts rumination vulnerability and mindfulness benefits

Sleep & Recovery

Sleep optimization through EEG pattern understanding:

- Alpha frequency predicts optimal sleep timing—higher frequency individuals are natural evening types

- Beta excess indicates need for longer wind-down periods before sleep

- Frontal theta activity correlates with sleep pressure and recovery needs

- Spindle frequency predicts sleep quality and memory consolidation efficiency

Applications for Personal Development

Pattern understanding enables targeted optimization across life domains:

- Work environment: Beta patterns predict optimal stimulation level, lighting, and background noise

- Learning strategies: Alpha/theta ratios indicate whether focused study or diffuse learning works better

- Exercise timing: Circadian alpha patterns predict when physical performance peaks

- Nutrition timing: Glucose metabolism affects EEG patterns—optimize meal timing for cognitive performance

- Social interaction: Temporal lobe patterns predict social energy and recovery needs

Future Directions

The field advances toward precision medicine approaches integrating genetic, environmental, and neurophysiological data:

- Machine learning models combining EEG phenotypes with genetic markers achieve >90% treatment prediction accuracy

- Longitudinal studies tracking phenotype stability across development and aging

- Integration with wearable EEG devices for real-time biofeedback and optimization

- Standardized protocols for clinical implementation across healthcare systems

- "Wild-type" database expansion including high-performing individuals, not just clinical populations

Get your own QEEG!

Want your own EEG analysis? Peak Brain Institute offers $249 assessments at locations in New York, Los Angeles, Orange County, and St. Louis. Remote program discounts available.

Have EEG data and want to learn interpretation? Check out this guide to reading your own QEEG!

Research Evidence Base

Key Studies on Resting EEG Patterns:

- Johnstone et al. (2005, Clinical EEG and Neuroscience): Phenotype framework development and validation

- Arns et al. (2008, Journal of Integrative Neuroscience): Treatment prediction using EEG phenotypes

- Clarke et al. (2001, Clinical Neurophysiology): ADHD subtype identification via quantitative EEG

- Monastra et al. (1999, Neuropsychology): Theta/beta ratio validation in attention disorders

- Davidson (1998, Psychophysiology): Frontal asymmetry and emotion regulation

Citations

- Arns, M., Gunkelman, J., Breteler, M., & Spronk, D. (2008). EEG phenotypes predict treatment outcome to stimulants in children with ADHD. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, 7(3), 421-438.

- Arns, M., Spronk, D., & Fitzgerald, P.B. (2010). Potential differential effects of 9 Hz rTMS and 10 Hz rTMS in the treatment of depression. Brain Stimulation, 3(2), 124-126.

- Berger, H. (1924). Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 87(1), 527-570.

- Bodenmann, S., Rusterholz, T., Dürr, R., Stoll, C., Bachmann, V., Geissler, E., et al. (2009). The functional Val158Met polymorphism of COMT predicts interindividual differences in brain alpha oscillations in young men. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(35), 10855-10862.

- Chabot, R.J., Orgill, A.A., Crawford, G., Harris, M.J., & Serfontein, G. (1999). Behavioral and electrophysiologic predictors of treatment response to stimulants in children with attention disorders. Journal of Child Neurology, 14(6), 343-351.

- Clarke, A.R., Barry, R.J., McCarthy, R., & Selikowitz, M. (2001). EEG-defined subtypes of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(11), 2098-2105.

- Davidson, R.J. (1998). Anterior electrophysiological asymmetries, emotion, and depression: Conceptual and methodological conundrums. Psychophysiology, 35(5), 607-614.

- Enoch, M.A., White, K.V., Harris, C.R., Rohrbaugh, J.W., & Goldman, D. (2002). The relationship between two intermediate phenotypes for alcoholism: Low voltage alpha EEG and low P300 ERP amplitude. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 509-517.

- Hegerl, U., Sander, C., Olbrich, S., & Schoenknecht, P. (2009). Are psychostimulants a treatment option in mania? Pharmacopsychiatry, 42(5), 169-174.

- Johnstone, J., Gunkelman, J., & Lunt, J. (2005). Clinical database development: Characterization of EEG phenotypes. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 36(2), 99-107.

- Khodayari-Rostamabad, A., Reilly, J.P., Hasey, G.M., de Bruin, H., & MacCrimmon, D.J. (2010). Using pre-treatment electroencephalography data to predict response to transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depression. Conference Proceedings IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2010, 6103-6106.

- Klimesch, W. (1999). EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews, 29(2-3), 169-195.

- Monastra, V.J., Lubar, J.F., Linden, M., VanDeusen, P., Green, G., Wing, W., et al. (1999). Assessing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder via quantitative electroencephalography: An initial validation study. Neuropsychology, 13(3), 424-433.

- Sander, C., Arns, M., Olbrich, S., & Hegerl, U. (2010). EEG-vigilance and response to stimulants in paediatric patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(9), 1511-1518.

- Spronk, D., Arns, M., Barnett, K.J., Cooper, N.J., & Gordon, E. (2011). An investigation of EEG, genetic and cognitive markers of treatment response to antidepressant medication in patients with major depressive disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(1-2), 41-48.

- Steriade, M., Gloor, P., Llinás, R.R., Lopes da Silva, F.H., & Mesulam, M.M. (1990). Report of IFCN committee on basic mechanisms. Basic mechanisms of cerebral rhythmic activities. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 76(6), 481-508.

- Suffin, S.C., & Emory, W.H. (1995). Neurometric subgroups in attentional and affective disorders and their association with pharmacotherapeutic outcome. Clinical Electroencephalography, 26(2), 76-83.

Related Articles

Biohacking Brain Fog: Restoring Mental Clarity

Your thoughts feel slow. Words don't come easily. You're staring at your computer screen, but nothing's happening—just mental static where clarity should be.

Biohacking Learning: Evidence-Based Skill Acquisition

Your brain's "factory settings" aren't optimized for learning. Discover evidence-based protocols for accelerated skill acquisition through neuroplasticity and strategic training.

Biohacking OCD: Targeting the Cortico-Striatal Circuit

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) isn't a character flaw or "just anxiety." It's a circuit dysfunction—hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) loop that cr...

About Dr. Andrew Hill

Dr. Andrew Hill is a neuroscientist and pioneer in the field of brain optimization. With decades of experience in neurofeedback and cognitive enhancement, he bridges cutting-edge research with practical applications for peak performance.

Get Brain Coaching from Dr. Hill →